Early history

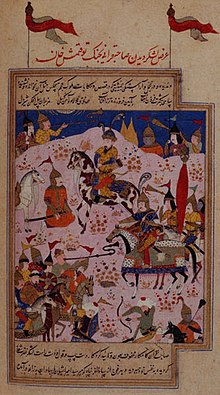

Emir Timur feasts in the gardens of

Samarkand.

At the age of eight or nine, Timur and his mother and brothers were carried as prisoners to Samarkand by an invading Mongol army.

In his childhood, Timur and a small band of followers raided travelers for goods, especially animals such as sheep, horses, and cattle.

[29] At around 1363, it is believed that Timur tried to steal a sheep from a shepherd but was shot by two arrows, one in his right leg and another in his right hand, where he lost two fingers. Both injuries caused him to be crippled for life. Some believe that Timur suffered his crippling injuries while serving as a mercenary to the khan of

Sistan in

Khorasan in what is known today as Dasht-i Margo (Desert of Death) in south-west Afghanistan. Timur's injuries have given him the name of Timur the Lame or Tamerlane by Europeans.

[30]

Timur was a Muslim, but while his chief official religious counsellor and advisor was the

Hanafi scholar 'Abdu 'l-Jabbar Khwarazmi, his particular persuasion is not known. In Tirmidh, he had come under the influence of his spiritual mentor

Sayyid Barakah, a leader from

Balkh who is buried alongside Timur in

Gur-e Amir.

[31][32][33] Timur was known to hold

Ali and the

Ahlul Bayt in high regard and has been noted by various scholars for his "pro-

Alid" stance.

[citation needed] Despite this, Timur was noted for attacking Shiites on Sunni grounds and therefore his own religious inclinations remain unclear.

[34]

Personality

Timur is regarded as a military genius and a tactician, with an uncanny ability to work within a highly fluid political structure to win and maintain a loyal following of nomads during his rule in Central Asia. He was also considered extraordinarily intelligent- not only intuitively but also intellectually.

[35] In Samarkand and his many travels, Timur, under the guidance of distinguished scholars was able to learn Persian, Mongolian, and Turkic languages.

[36] More importantly, Timur was characterized as an opportunist. Taking advantage of his Turco-Mongolian heritage, Timur frequently used either the Islamic religion or the law and traditions of the Mongol Empire to achieve his military goals or domestic political aims.

[37][38]

Military leader

In about 1360 Timur gained prominence as a military leader whose troops were mostly Turkic tribesmen of the region.

[26][39]He took part in campaigns in

Transoxiana with

the Khan of

Chagatai. His career for the next ten or eleven years may be thus briefly summarized from the

Memoirs. Allying himself both in cause and by family connection with Kurgan, the dethroner and destroyer of

Volga Bulgaria, he was to invade

Khorasan at the head of a thousand horsemen. This was the second military expedition that he led, and its success led to further operations, among them the subjugation of

Khorezm and

Urganj.

Following Kurgan's murder, disputes arose among the many claimants to

sovereign power; this infighting was halted by the invasion of the energetic Chagtaid

Tughlugh Timur of

Kashgar, another descendant of Genghis Khan. Timur was dispatched on a mission to the invader's camp, which resulted in his own appointment to the head of his own tribe, the

Barlas, in place of its former leader,

Hajji Beg.

The exigencies of Timur's quasi-sovereign position compelled him to have recourse to his formidable patron, whose reappearance on the banks of the

Syr Darya created a consternation not easily allayed. One of Tughlugh's sons was entrusted with the Barlas's territory, along with the rest of

Mawarannahr (Transoxiana), but he was defeated in battle by the bold warrior he had replaced, at the head of a numerically far inferior force.

Rise to power

It was in this period that Timur reduced the

Chagatai khans to the position of

figureheads while he ruled in their name. During this period, Timur and his brother-in-law Husayn, who were at first fellow fugitives and wanderers in joint adventures, became rivals and antagonists. The relationship between them began to become strained after Husayn abandoned efforts to carry out Timur's orders to finish off Ilya Khoja (former governor of Mawarannah) close to Tishnet.

[40]

Timur began to gain a following of people in Balkh that consisted of merchants, fellow tribesmen, Muslim clergy, aristocracy and agricultural workers because of his kindness in sharing his belongings with them, as contrasted with Husayn, who alienated these people, took many possessions from them via his heavy tax laws and selfishly spent the tax money building elaborate structures.

[41] At around 1370 Husayn surrendered to Timur and was later assassinated by a chief of a tribe, which allowed Timur to be formally proclaimed sovereign at

Balkh. He married Husayn's wife

Saray Mulk Khanum, a descendant of Genghis Khan, allowing him to become imperial ruler of the Chaghatay tribe.

[42]

One day Aksak Temür spoke thusly:

"Khan Züdei (in China) rules over the city. We now number fifty to sixty men, so let us elect a leader." So they drove a stake into the ground and said: "We shall run thither and he among us who is the first to reach the stake, may he become our leader". So they ran and Aksak Timur, as he was lame, lagged behind, but before the others reached the stake he threw his cap onto it. Those who arrived first said: "We are the leaders." ["But,"] Aksak Timur said: "My head came in first, I am the leader." Meanwhile, an old man arrived and said: "The leadership should belong to Aksak Timur; your feet have arrived but, before then, his head reached the goal." So they made Aksak Timur their prince.

[43][44]

Legitimization of Timur's rule

Timur's Turco-Mongolian heritage provided opportunities and challenges as he sought to rule the Mongol Empire and the Muslim world. According to the Mongol traditions, Timur could not claim the title of

khan or rule the Mongol Empire because he was not a descendant of Genghis Khan. Therefore, Timur set up a puppet Chaghatay khan, Suyurghatmish, as the nominal ruler of Balkh as he pretended to act as a "protector of the member of a Chinggisid line, that of Chinggis Khan's eldest son, Jochi."

[45]

As a result, Timur never used the title of

khan because the name khan could only be used by those who come from the same lineage as Genghis Khan himself. Timur instead used the title of

amir meaning general, and acting in the name of the

Chagatairuler of Transoxania.

[46]

To reinforce his position in the Mongol Empire, Timur managed to acquire the royal title of son-in-law when he married a princess of Chinggisid descent.

[47]

Likewise, Tamerlane could not claim the supreme title of the Islamic world, caliph, because the “office was limited to the Quraysh, the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad.”

[48] Therefore, Tamerlane reacted to the challenge by creating a myth and image of himself as a “supernatural personal power””

[48] ordained by God. Since Tamerlane had a successful career as a conqueror, it was easy to justify his rule as ordained and favored by God since no ordinary man could be a possessor of such good fortune that resistance would be seen as opposing the will of Allah. Moreover, the Islamic notion that military and political success was the result of Allah’s favor had long been successfully exploited by earlier rulers. Therefore, Tamerlane’s assertions would not have seemed unbelievable to his fellow Islamic people.

Period of expansion

Timur besieges the historic city of

Urganj.

Emir Timur's army attacks the survivors of the town of Nerges, in Georgia, in the spring of 1396.

Timur spent the next 35 years in various

wars and expeditions. He not only consolidated his rule at home by the subjugation of his foes, but sought extension of territory by encroachments upon the lands of foreign potentates. His conquests to the west and northwest led him to the lands near the

Caspian Sea and to the banks of the

Ural and the

Volga. Conquests in the south and south-West encompassed almost every province in

Persia, including

Baghdad,

Karbala and Northern Iraq.

One of the most formidable of Timur's opponents was another Mongol ruler, a descendant of Genghis Khan named

Tokhtamysh. After having been a refugee in Timur's court,

Tokhtamysh became ruler both of the eastern

Kipchak and the

Golden Horde. After his accession, he quarrelled with Timur over the possession of

Khwarizm and

Azerbaijan. However, Timur still supported him against the Russians and in 1382 Tokhtamysh invaded the Muscovite dominion and burned

Moscow.

[49]

After the death of

Abu Sa'id, ruler of the

Ilkhanid Dynasty, in 1335, there was a power vacuum in Persia. In 1383, Timur started the military conquest of Persia. He captured

Herat, Khorasan and all eastern Persia by 1385; he captured almost all of Persia by 1387. Of note during the Persian campaign was the capture of

Isfahan. When

Isfahan surrendered to Timur in 1387, he treated it with relative mercy as he normally did with cities that surrendered. However, after the city revolted against Timur's taxes by killing the tax collectors and some of Timur's soldiers. Timur ordered the massacre of the city's citizens with the death toll reckoned at between 100,000 and 200,000.

[50] An eye-witness counted more than 28 towers constructed of about 1,500 heads each.

[51] This has been described as a "systematic use of terror against towns...an integral element of Tamerlane's strategic element" which he viewed as preventing bloodshed by discouraging resistance. His massacres were selective and he spared the artistic and technical (e.g. engineers) elites.

[50]

In the meantime Tokhtamysh, now khan of the

Golden Horde, turned against his patron and in 1385 invaded

Azerbaijan. The inevitable response by Timur resulted in the

Tokhtamysh–Timur war. In the initial stage of the war Timur won a victory at the

Battle of the Kondurcha River. After the battle Tokhtamysh and some of his army were allowed to escape. After Tokhtamysh's initial defeat Timur then invaded Muscovy to the north of Tokhtamysh's holdings. Timur's army burned

Ryazan and advanced on Moscow. He was then pulled away before reaching the Oka River by Tokhtamysh's renewed campaign in the south.

[49]

In the first phase of the conflict with Tokhtamysh, Timur led an army of over 100,000 men north for more than 700 miles into the steppe. He then rode west about 1,000 miles advancing in a front more than 10 miles wide. During this advance Timur's army got far enough north to be in a region of

very long summer days causing complaints by his Muslim soldiers about keeping a long schedule of

prayers.It was then that Tokhtamysh's army was boxed in against the east bank of the Volga River in the

Orenburg region and destroyed at the

Battle of the Kondurcha River.

It was in the second phase of the conflict that Timur took a different route against the enemy by invading the realm of Tokhtamysh via the

Caucasus region. The year 1395 saw the

Battle of the Terek River concluding the titanic struggle between the two monarchs.

Tokhtamysh was not able to restore his power or prestige. He was killed about a decade after the Terek River battle in the area of present day

Tyumen.

During the course of Timur's campaigns his army destroyed

Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde, and

Astrakhan, subsequently disrupting the Golden Horde's

Silk Road. The Golden Horde no longer held power after the coming of Tamerlane.

In May 1393 Timur's army invaded the

Anjudan. This crippled the

Ismaili village only one year after his assault on the Ismailis in

Mazandaran. The village was prepared for the attack. This is evidenced by it containing a fortress and a system of underground tunnels. Undeterred, Timur’s soldiers flooded the tunnels by cutting into a channel overhead. Timur’s reasons for attacking this village are not yet well-understood. However, it has been suggested that his

religious persuasions and view of himself as an

executor of divine will may have contributed to his motivations.

[52] The Persian historian

Khwandamir explains that an Ismaili presence was growing more politically powerful in Persian

Iraq. A group of locals in the region was dissatisfied with this and, Khwandamir writes, these locals assembled and brought up their complaint with Timur, possibly provoking his attack on the Ismailis there.

[52]

Campaign against the Tughlaq Dynasty

Timur defeats the

Sultan of Delhi, Nasir Al-Din Mahmud Tughluq, in the winter of 1397–1398, painting dated 1595–1600.

He justified his campaign towards Delhi as a religious war against the

Hindureligion practiced in the city and also as a chance for to gain more riches in a city that was lacking control.

[57] By all accounts, Timur's campaigns in India were marked by systematic slaughter and other atrocities on a truly massive scale inflicted mainly on the subcontinent's Hindu population.

[58]

Timur crossed the Indus River at

Attock (now

Pakistan) on 24 September 1398. His invasion did not go unopposed and he encountered resistance by the Governor of

Meerut during the march to Delhi. Timur was still able to continue his approach to Delhi, arriving in 1398, to fight the armies of Sultan Nasir-ud-Din Mahmud Shah Tughluq, which had already been weakened by a succession struggle within the royal family.

Capture of Delhi (1398)

The battle took place on 17 December 1398. Sultan Nasir-ud-Din Mahmud Shah Tughluq and Mallu Iqbal's

[59] army had war elephants armored with chain mail and poison on their tusks.

[60] With his Tatar forces afraid of the elephants, Timur ordered his men to dig a trench in front of their positions. Timur then loaded his camels with as much wood and hay as they could carry. When the war elephants charged, Timur set the hay on fire and prodded the camels with iron sticks, causing them to charge at the elephants howling in pain: Timur had understood that elephants were easily panicked. Faced with the strange spectacle of camels flying straight at them with flames leaping from their backs, the elephants turned around and stampeded back toward their own lines. Timur capitalized on the subsequent disruption in Nasir-ud-Din Mahmud Shah Tughluq's forces, securing an easy victory. Delhi was sacked and left in ruins. Before the battle for Delhi, Timur executed 100,000 captives:

[11][53]

The capture of the Delhi Sultanate was one of Timur's greatest victories, arguably surpassing the likes of

Alexander the Greatand Genghis Khan because of the harsh conditions of the journey and the achievement of taking down one of the richest cities at the time.

[61]

After Delhi fell to Timur's army, uprisings by its citizens against the Turkic-Mongols began to occur, causing a bloody massacre within the city walls. After three days of citizens uprising within Delhi, it was said that the city reeked of decomposing bodies of its citizens with their heads being erected like structures and the bodies left as food for the birds.

[62]

Timur's invasion and destruction of Delhi continued the chaos that was still consuming India and the city would not be able to recover from the great loss it suffered for almost a century.

[63]

Campaigns in the Levant

Before the end of 1399, Timur started a war with

Bayezid I, sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the

Mamluksultan of Egypt

Nasir-ad-Din Faraj. Bayezid began annexing the territory of Turkmen and Muslim rulers in

Anatolia. As Timur claimed sovereignty over the

Turkmen rulers, they took refuge behind him. Timur invaded Syria, sacked

Aleppo and captured

Damascus after defeating the Mamluk army. The city's inhabitants were massacred, except for the artisans, who were deported to Samarkand.

He invaded Baghdad in June 1401. After the capture of the city, 20,000 of its citizens were massacred. Timur ordered that every soldier should return with at least two severed human heads to show him. (Many warriors were so scared they killed prisoners captured earlier in the campaign just to ensure they had heads to present to Timur.)

[citation needed]

Shakh-i Zindeh mosque, Samarkand.

In the meantime, years of insulting letters had passed between Timur and Bayezid. Finally, Timur invaded Anatolia and defeated Bayezid in the

Battle of Ankara on 20 July 1402. Bayezid was captured in battle and subsequently died in captivity, initiating the twelve-year

Ottoman Interregnum period. Timur's stated motivation for attacking Bayezid and the Ottoman Empire was the restoration of

Seljuq authority. Timur saw the Seljuks as the rightful rulers of

Anatolia as they had been granted rule by Mongol conquerors, illustrating again Timur's interest with Genghizid legitimacy.

After the Ankara victory, Timur's army ravaged Western Anatolia, with Muslim writers complaining that the Timurid army acted more like a horde of savages than that of a civilized conqueror.

[citation needed] But Timur did take the city of Smyrna, a stronghold of the Christian

Knights Hospitalers, thus he referred to himself as

ghazi or "Warrior of Islam".

Timur was furious at the

Genoese and

Venetians whose ships ferried the Ottoman army to safety in

Thrace. As

Lord Kinrossreported in

The Ottoman Centuries, the Italians preferred the enemy they could handle to the one they could not.

While Timur invaded Anatolia,

Qara Yusuf assaulted Baghdad and captured it in 1402. Timur returned to Persia from Anatolia and sent his grandson Abu Bakr ibn Miran Shah to reconquer Baghdad, which he proceeded to do. Timur then spent some time in

Ardabil, where he gave

Ali Safavi, leader of the

Safaviyya, a number of captives. Subsequently, he marched to Khorasan and then to Samarkhand, where he spent nine months celebrating and preparing to invade Mongolia and China.

[65]

He ruled over an empire that, in modern times, extends from southeastern

Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and

Iran, through

Central Asiaencompassing part of

Kazakhstan,

Afghanistan,

Armenia,

Azerbaijan,

Georgia,

Turkmenistan,

Uzbekistan,

Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and even approaches

Kashgar in China. The conquests of Timur are claimed to have caused the deaths of up to 17 million people, an assertion impossible to verify.

[66] Timur's campaigns sometimes caused large and permanent demographic changes. Northern Iraq remained predominantly

Assyrian Christian until attacked, looted, plundered and destroyed by Timur, leaving its population decimated by systematic mass slaughter.

[67]

Of Timur's four sons, two (Jahangir and Umar Shaykh) predeceased him. His third son,

Miran Shah, died soon after Timur, leaving the youngest son, Shah Rukh. Although his designated successor was his grandson

Pir Muhammad b. Jahangir, Timur was ultimately succeeded in power by his son Shah Rukh. His most illustrious descendant

Babur founded the Islamic

Mughal Empire and ruled over most of

Afghanistan and

North India. Babur's descendants

Humayun,

Akbar,

Jahangir,

Shah Jahan and

Aurangzeb, expanded the Mughal Empire to most of the

Indian subcontinent.

Markham, in his introduction to the narrative of Clavijo's embassy, states that his body "was embalmed with musk and rose water, wrapped in linen, laid in an ebony coffin and sent to Samarkand, where it was buried." His tomb, the

Gur-e Amir, still stands in Samarkand, though it has been heavily restored in recent years.

Attempts to attack the Ming Dynasty

The fortress at

Jiayuguan (pass) was strengthened due to fear of an invasion by Timur, while he led an army towards China.

[68]

By 1368 the new Chinese

Ming Dynasty had driven the

Mongols out of

China. The first

Ming Emperor

Hongwu and his successor

Yongledemanded, and received, homage from many Central Asian states as the political heirs to the former House of

Kublai. The Ming emperor's treatment of Timur as a

vassal did not sit well with the conqueror. In 1394 Hongwu's ambassadors eventually presented Timur with a letter addressing him as a subject. He summarily had the ambassadors

Fu An, Guo Ji, and Liu Wei detained. He then had them and their 1,500 guards executed.

[69] Neither Hongwu's next ambassador,

Chen Dewen(1397) nor the delegation announcing the accession of the Yongle Emperor fared any better.

[69]

Timur eventually planned to conquer China. To this end Timur made an alliance with the

Mongols of the

Northern Yuan Dynastyand prepared all the way to Bukhara. The Mongol leader

Enkhe Khan sent his grandson

Öljei Temür, also known as Buyanshir Khan after he converted to

Islam while he stayed at the court of Timur in Samarkand.

[70] In December 1404 Timur started military campaigns against the Ming Dynasty and detained a Ming envoy. But he was attacked by fever and plague when encamped on the farther side of the Sihon (

Syr-Daria) and died at Atrar (

Otrar) on 17 February 1405

[71] before ever reaching the Chinese border.

[72] Only after that were the Ming envoys released.

[69]

Timur preferred to fight his battles in the spring. However, he died en route during an uncharacteristic winter campaign against the ruling Chinese

Ming Dynasty. It was one of the bitterest winters on record. His troops are recorded as having to dig through five feet of ice to reach drinking water.

Exchanges with Europe

Timur had numerous epistolary and diplomatic exchanges with various European states, especially Spain and France.

Relations between the court of

Henry III of Castile and that of Timur played an important part in medieval Spanish

Castilian diplomacy. In 1402, the time of the Battle of Ankara, two Spanish ambassadors were already with Timur: Pelayo de Sotomayor and Fernando de Palazuelos. Later, Timur sent to the court of

Castile and

León a

Chagatay ambassador named

Hajji Muhammad al-Qazi with letters and gifts.

In return, Henry III of Castile sent a famous embassy to Timur's court in Samarkand in 1403–06, led by

Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo, with two other ambassadors, Alfonso Paez and Gomez de Salazar. On their return, Timur affirmed that he regarded the king of Castile "as his very own son".

According to Clavijo, Timur's good treatment of the Spanish delegation contrasted with the disdain shown by his host toward the envoys of the "lord of

Cathay" (i.e., the

Ming DynastyYongle Emperor), the Chinese ruler. Clavijo's visit to Samarkand allowed him to report to the European audience on the news from

Cathay (China), which few Europeans had been able to visit directly in the century that had passed since the travels of

Marco Polo.

The French archives preserve:

- A 30 July 1402 letter from Timur to Charles VI of France, suggesting that he send traders to the Orient. It is written in Persian.[73]

- A May 1403 letter. This is a Latin transcription of a letter from Timur to Charles VI, and another from Amiza Miranchah, his son, to the Christian princes, announcing their victory over Bayezid, in Smyrna.[74]

A copy has been kept of the answer of Charles VI to Timur, dated 15 June 1403.

[75]

European Views on Timur

Timur arguably had the most impact on the Renaissance culture and early modern Europe.

[76] Timur's achievements have both fascinated and horrified Europeans from the fifteenth century to the early nineteenth century.

European views of Timur were mixed throughout the fifteenth century with some European countries calling him an ally, while others saw him as a threat to Europe because of his rapid expansion and brutality.

[77]

When Timur took down the Ottoman Sultan

Bayezid at

Ankara, he was often praised and seen as a trusted ally by European rulers such as

Charles VI of France and

Henry IV of England because they believe he was saving Christianity from the Turkish Empire in the Middle East. Charles VI of France and Henry IV of England also praised Timur because his victory at Ankara allowed Christian merchants to remain in the Middle East and allowed for their safe return home to both France and England. Timur was also praised because it is believed that he helped restore the right of passage for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land.

[78]

Some European countries viewed Timur as a barbaric enemy who presented a threat to both European culture and the religion of Christianity. Timur's rise to power moved many leaders, such as Henry III of Castille, to send embassies to Samarkand to personally scout out Timur, learn about his people, make alliances with him and to try to convince him to convert to Christianity in order to avoid war.

[79]

Legacy

I am not a man of blood; and God is my witness that in all my wars I have never been the aggressor, and that my enemies have always been the authors of their own calamity.

Timur's legacy is a mixed one. While Central Asia blossomed under his reign, other places such as

Baghdad,

Damascus,

Delhiand other Arab,

Georgian, Persian, and Indian cities were sacked and destroyed and their populations massacred. He was responsible for the effective destruction of the Christian Church in much of Asia. Thus, while Timur still retains a positive image in Muslim Central Asia, he is vilified by many in

Arabia, Persia, and

India, where some of his greatest atrocities were carried out. However,

Ibn Khaldun praises Timur for having unified much of the Muslim world when other conquerors of the time could not.

[81]

Timur's military talents were unique. He planned all his campaigns years in advance, even planting barley for horse feed two years ahead of his campaigns. He used

propaganda, in what is now called

information warfare, as part of his tactics. His campaigns were preceded by the deployment of spies whose tasks included collecting information and spreading horrifying reports about the cruelty, size, and might of Timur’s armies. Such psychological warfare eventually weakened the morale of threatened populations and caused panic in the regions that he intended to invade.

[citation needed]

For his time he had an uncharacteristic concern for his troops which inspired fierce loyalty from them. They were not paid, however; instead their incentives were from looting captured territory—a bounty that included horses, women, precious metals and stones; in other words whatever they, or their newly captured slaves, could carry away from the conquered lands.

[citation needed]

Timur's short-lived empire also melded the

Turko-Persian tradition in

Transoxiania, and in most of the territories which he incorporated into his

fiefdom,

Persian became the primary

language of administration and literary culture (

diwan), regardless of

ethnicity.

[82] In addition, during his reign, some contributions to Turkic literature were penned, with Turkic cultural influence expanding and flourishing as a result. A literary form of

Chagatai Turkic came into use alongside Persian as both a cultural and an official language.

[83]

Timur became a relatively popular figure in Europe for centuries after his death, mainly because of his victory over the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid. The Ottoman armies were at the time invading Eastern Europe and Timur was ironically seen as a sort of ally.

Timur has now been officially recognized as a national hero of newly independent

Uzbekistan. His monument in Tashkent now occupies the place where

Marx's statue once stood.

The

Sharif of the

Hijaz suffers due to the divisive sectarian schisms of his faith, And lo! that young

Tatar (Timur) has boldly re-envisioned magnanimous victories of overwhelming conquest.

Biographies

Timur's generally recognised biographers are Ali Yazdi, commonly called

Sharaf ud-Din, author of the

Zafarnāmeh (

Persian:

ظفرنامه), translated by Petis de la Croix in 1722, and from

French into

English by J. Darby in the following year; and Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Abdallah, al-Dimashiqi, al-Ajami (commonly called

Ahmad Ibn Arabshah) translated by the Dutch Orientalist Colitis in 1636. In the work of the former, as

Sir William Jones remarks, "the Tatarian conqueror is represented as a liberal, benevolent and illustrious prince", in that of the latter he is "deformed and impious, of a low birth and detestable principles." But the favourable account was written under the personal supervision of Timur's grandson, Ibrahim, while the other was the production of his direst enemy.

Among less reputed biographies or materials for biography may be mentioned a second

Zafarnāmeh, by Nizam al-Din Shami, stated to be the earliest known history of Timur, and the only one written in his lifetime. Timur's purported autobiography, the

Tuzk-e-Taimuri ("Memoirs of Temur") is a later fabrication, although most of the historical facts are accurate.

[11]

More recent biographies include

Justin Marozzi's

Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World (2006)

[85] and Roy Stier's

Tamerlane: The Ultimate Warrior (1998).

[86]

Exhumation

A forensic facial reconstruction of Timur by

M. Gerasimov (1941).

Timur's body was

exhumed from his tomb in 1941 by the

Soviet anthropologist Mikhail M. Gerasimov. From his bones it was clear that Timur was a tall and broad chested man with strong cheek bones. Gerasimov reconstructed the likeness of Timur from his skull. At 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 meters), Timur was tall for his era.

[citation needed] Gerasimov also confirmed Timur's lameness due to a hip injury. Gerasimov found that Timur's facial characteristics conformed to that of Asiatic features with Caucasian admixture.

[71]

It is alleged that Timur's tomb was inscribed with the words, "When I rise from the dead, the world shall tremble." It is also said that when Gerasimov exhumed the body, an additional inscription inside the casket was found reading, "Who ever opens my tomb, shall unleash an invader more terrible than I."

[87] In any case, two days after Gerasimov had begun the exhumation, Adolf Hitler launched

Operation Barbarossa, the largest military invasion of all time, upon the U.S.S.R.

[88] Timur was re-buried with full Islamic ritual in November 1942 just before the Soviet victory at the

Battle of Stalingrad.

[89]

In the arts

- Tamburlaine the Great, Parts I and II (English, 1563–1594): play by Christopher Marlowe

- Tamerlane (1701): play by Nicholas Rowe (English)

- Tamerlano (1724): opera by George Frideric Handel, in Italian, based on the 1675 play Tamerlan ou la mort de Bajazetby Jacques Pradon.

- Bajazet (1735): opera by Antonio Vivaldi, portrays the capture of Bayezid I by Timur

- Il gran Tamerlano (1772): opera by Josef Mysliveček that also portrays the capture of Bayezid I by Timur

- Tamerlane: first published poem of Edgar Allan Poe (American, 1809–1849).

- Timur is the deposed, blind former King of Tartary and father of the protagonist Calaf in the opera Turandot (1924) byGiacomo Puccini, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni.

- Timour appears in the story Lord of Samarkand by Robert E. Howard.

- Tamerlan: novel by Colombian writer Enrique Serrano in Spanish[90]

- Timur Lang is also the name of the warlord that shall be defeated in the game Might and Magic IX, a sort of joke using the names of Timur Leng and this game's designer's one, Timothy Lang.

- Timur is featured in the "Mongols" episode of the History Channel miniseries Barbarians.

- Tamerlan appears in the Russian movie Dnevnoy Dozor (Day Watch), in which he steals the chalk of fate.

- Tamerlane is the name of the corporation which is taking over Central Asia in the 2008 satire War, Inc.

- Tamburlaine: Shadow of God: a BBC Radio 3 play by John Fletcher, broadcast 2008, is a fictitious account of an encounter between Tamburlaine, Ibn Khaldun, and Hafez.

- Tamerlane (1928): historical novel by Harold Lamb.

Gallery

Geometric courtyard surrounding the tomb showing the Iwan, and dome.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+Proud+of+Mithila.jpgJPG)